Indre Viskontas on the Intersection of Music and Neuroscience

SFCM faculty member Indre Viskontas (Class of ’08) is a Renaissance woman of sorts. She’s a neuroscientist, author, and opera singer, often finding herself mixing them all together in the educational and artistic pursuits that she finds most compelling. She has most recently been studying music’s effect on the brain, and in early April, will release How Music Can Make You Better, a book that traverses our interaction with music on both molecular and societal levels.

In this Q&A, Viskontas fills us in on the story behind this new publication, tells us about her interest in music and the brain, and what’s on the horizon for her.

What initially inspired you to study music's effect on the brain?

For a long time, I kept my two passions—opera and neuroscience—separate, worried that one would tarnish the other. When it came to music, I felt that taking a reductionist perspective, which is necessary for sound scientific inquiry, would throw the baby out with the bathwater. So instead, I approached the intersection from the opposite direction: what can music tell us about the mind? That's what led to the creation of my podcast, Cadence, which explores the mind through our obsession with music, and eventually to this book.

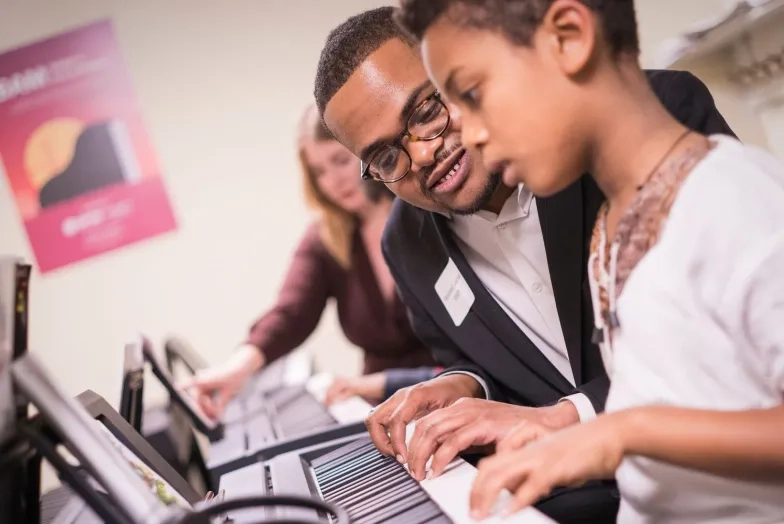

But having developed expertise in how the brain changes with training—I did my PhD research on neuroplasticity related to memory formation—I also realized that applying the principles of learning to my own musical training would make my practice more efficient. And so I created one of the courses I teach at SFCM (“Training the Musical Brain”) with that in mind. I explain the neuroscience of learning and memory to our students, and then, together, we develop more effective practice strategies and hopefully embark on a lifetime of productive and variable practice.

How do you balance your career as a singer, neuroscientist, podcast host, etc.?

Just like any artist, I enjoy wearing multiple hats. My hats just include science and science communication in addition to music. I've learned over the years to prioritize and to work on projects one at a time. So I plan about three to five years out, creating space for each of the endeavors that I find most compelling, but being open to pivoting if a great opportunity (like this book) presents itself. Some things I do every week to keep those muscles active, like singing and writing. And I tend to choose activities that are complementary. It's not that different to present a recital and give a great keynote presentation. There's a lot of overlap. So I try to be strategic about which projects I commit to and, also, I'm very mindful and miserly when spending my most precious resource: time.

How have you been able to apply what you learned as a student at SFCM to this book and to your research?

Most definitely. Being a student at SFCM gave me an insider's view of what it takes to become a professional musician and how different people tackle the same obstacles. I also made a lot of connections with musicians, many of whom remain my best friends and colleagues today.

What do you hope people will take away from reading this book?

This book is really about exposing aspects of the musical experience, be it listening, playing, or even using it therapeutically, that we don't often consider very deeply. But also to dismiss the notion that you must be an expert to “get” music. We're all experts at extracting meaning from sound—we just do it in ways that reflect our personal experience and sonic education. So my hope is that readers will recognize themselves in many of the descriptions I provide of how music shapes us and affects us. And that they might discover new ways of incorporating music into their lives. Because life—everything really—is just better with music.

How did the commission to write this book come about?

Chronicle Books had begun the How series with a book called How Art Can Make You Happy. It's their attempt to address the fact that many of the arts have become somewhat elitist. Going to an art gallery filled with abstract modern art can feel intimidating, just like going to the opera or symphony can also make some people uncomfortable because they don't know what to look or listen for and therefore feel excluded.

My podcast, Cadence: what music tells us about the mind, has a similar goal: to expose the various ways that music affects us and to make knowledge both about the brain and music accessible to everyone. The second season of Cadence was all about how music can be used as medicine. We told eight stories of different individuals, ranging from impoverished women to kids with cancer or on the autism spectrum to older adults suffering from Parkinson's disease, and how music has changed their trajectories for the better. One of the editors at Chronicle listened to the podcast and felt that it would make a great sequel to How Art Can Make You Happy, and so we met and drafted a book proposal and here we are!

What's next for you?

Well, I have a few exciting projects coming up. I'm currently working on my third set of lectures for The Great Courses, this time called How Technology is Shaping How We Think. We're aiming to film those in the fall and then I hope to turn many of those ideas into a book. And in January, at Pasadena Opera, where I'm the Creative Director, we'll be presenting our first commission, The Bloody Chamber, a feminist retelling of the Bluebeard Castle fairytale, based on the novel by Angela Carter. It's being written by NYC-based composer Daniel Felsenfeld who happens to be writing it with my voice in mind for the character of Dora, the new bride who has the run of the palace but must never enter one room. It's a psychological thriller that explores the themes of power and intimacy and how each of us is better off with a little part of our psyche that we keep to ourselves. It's a great example of how we can better understand our own minds through music.