SFCM Chamber Orchestra - Beethoven Interpolations

Program

Pamela Z (world premiere; SFCM commission)

Heiligenstadt Lament

Webern

Symphony, Op. 21

Dallapiccola

Piccola musica notturna

Anna Thorvaldsdottir

aequilibria

Movements from Beethoven’s First Symphony, Op. 21 will be interspersed throughout the performance.

Performers

SFCM Chamber Orchestra

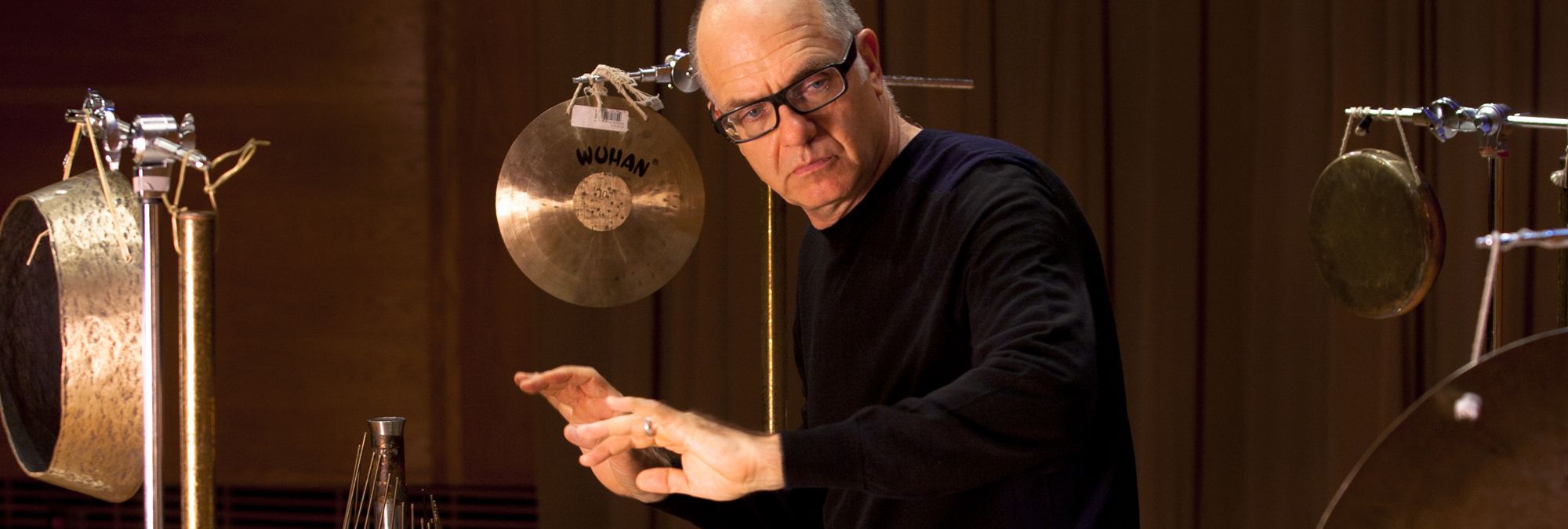

Steven Schick, guest conductor

Artist Profiles

Percussionist, conductor, and author Steven Schick was born in Iowa and raised in a farming family. Hailed by Alex Ross in the New Yorker as, “one of our supreme living virtuosos, not just of percussion but of any instrument,” he has championed contemporary percussion music by commissioning or premiering more than one hundred-fifty new works. The most important of these have become core repertory for solo percussion. Steven Schick is artistic director of the La Jolla Symphony and Chorus and the Breckenridge Music Festival. With Claire Chase, he is co-artistic director of the Summer Music Program at Banff Center in Canada. Also active as a conductor, he has appeared with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra the Milwaukee Symphony, Ensemble Modern, the International Contemporary Ensemble, and the Asko/Schönberg Ensemble. In 2018 he curated and was conductor and percussion soloist in, “It’s About Time,” a festival of the San Diego Symphony designed to highlight the musical dimensions of the cross-border area. Schick’s publications include a book, “The Percussionist’s Art: Same Bed, Different Dreams,” and numerous recordings including the 2010 “Percussion Works of Iannis Xenakis,” and its companion, “The Complete Early Percussion Works of Karlheinz Stockhausen” in 2014 (Mode). For the latter, he received the Deutscheschallplattenkritikpreis for the best new music release of 2015. He was inducted into the Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame in 2014. Steven Schick is Distinguished Professor of Music and holds the Reed Family Presidential Chair at the University of California, San Diego.

Pamela Z is a composer/performer and media artist who works primarily with voice, live electronic processing, sampled sound, and video. A pioneer of live digital looping techniques, she processes her voice in real time to create dense, complex sonic layers. Her solo works combine experimental extended vocal techniques, operatic bel canto, found objects, text, digital processing, and wireless MIDI controllers that allow her to manipulate sound with physical gestures. In addition to her solo work, she has been commissioned to compose scores for dance, theatre, film, and chamber ensembles including Kronos Quartet, the Bang on a Can All Stars, Ethel, and San Francisco Contemporary Music Players. Her interdisciplinary performance works have been presented at venues including The Kitchen (NY), Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (SF), REDCAT (LA), and MCA (Chicago), and her installations have been presented at such exhibition spaces as the Whitney (NY), the Diözesanmuseum (Cologne), and the Krannert (IL). Pamela Z has toured extensively throughout the US, Europe, and Japan. She has performed in numerous festivals including Bang on a Can at Lincoln Center (New York), Interlink (Japan), Other Minds (San Francisco), La Biennale di Venezia (Italy), Dak’Art (Sénégal) and Pina Bausch Tanztheater Festival (Wuppertal, Germany). She is the recipient of numerous awards including a Robert Rauschenberg Foundation residency, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Doris Duke Artist Impact Award, Herb Alpert Award in the Arts, an Ars Electronica honorable mention, and the NEA Japan/US Friendship Commission Fellowship. She holds a music degree from the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Conductor's Note

Ernest Hemingway reportedly expressed his disdain for the music of George Antheil by quipping, “Thank you, but I prefer my Stravinsky straight!”

So, what do I say to those listeners who prefer their Beethoven straight? One response might be that the meaning of “straight” has changed. Beethoven would scarcely recognize today’s typical concert of classical music. Only in the relatively recent past has the concert experience become a super-serious event in stadium seating where entire pieces are presented without interruption before a large, respectful (and largely silent) audience. In his day, concerts were often cacophonous events, where small pieces—solos, humorous ditties and the like—were interspersed among the movements of a main piece as a backdrop to often boisterous conversations among audience members.

This afternoon’s concert is not an invitation for audience hijinks! But we are building on the classical notion of interpolation to shed some light on Beethoven’s impact on 20th and 21st music. Therefore, presented among the movements of Beethoven’s mercurial First Symphony (1800) are pieces that contain some 20th and 21st century echoes of Beethoven’s mind. They represent Beethoven’s formalism, his penchant for lyricism, and his wicked sense of humor. And they afford insight into parallel moments of cultural and political peril. From the turn of the 19th century in post-revolutionary Europe to the volatile time between world wars in the 20th century to our contemporary michigas, these works, taken together, demonstrate the necessity for an artist to react to her or his time.

Here’s a personal memory: I was a rehearsing a Beethoven-inspired passage in George Crumb with the brilliant director Peter Sellars and the oracular pianist Gil Kalish. Gil, who could turn a musical phrase as well as anyone I ever worked with, was toying with a cadence point when Peter remarked, “Gil, this phrase needs a little crisis.” Kalish responded with his usual sophistication, and in that moment the music stopped sounding like Crumb and began to evoke Beethoven. Indeed, the management of crisis—in other words the constant negotiation between turmoil and equipoise—is a critical skill in the interpretation of Beethoven.

We unpack that idea in the two newer works that frame our concert. We’ll start with the first performance Pamela Z’s Heiligenstadt Lamentation—this is a San Francisco Conservatory of Music commission--with the composer as vocal soloist. Here we imagine the relatively happy period in Beethoven’s life (relative is the operative word here) just before his encroaching deafness threatened to change everything. Pamela Z reflects the increasing chaos in Beethoven’s aural life through overlaid looping and real-time processing of her voice. By posing the unfathomable prospect of deafness even before we hear the very first note of his very first symphony, we seek to cast the First Symphony, not as the light-weight romp it sometimes (incorrectly) seems, but as something truly seminal. And as a valedictory statement, we offer Anna Thorvaldsdottir’s aptly-named Aequilibria to remind us that, no matter how painful his travails may have been, Beethoven was at his essence a classicist, for whom balance and equilibrium were the abiding tokens of aesthetic expression.

And what do we make of Beethoven’s radical understanding of democracy? The famous Schiller text, An die Freude, which Beethoven carried with him nearly all of his life and which was set, unforgettably, in his Ninth Symphony, remains palatable to nearly every modern listener. But Beethoven, in spiritual league with the flame-throwing radicals of the Jacobin, turned his back on princes and emperors. What might he have said of today’s cultural aristocracy in the form of the well-heeled gala crowd of a contemporary symphony orchestra?

Therefore, the center works of today’s performance—Anton Webern’s Symphony, Op. 21 and Luigi Dallapiccola’s haunting Una Piccola Musica Notturna—represent Beethoven the egalitarian. The politics of neither mid 20th century composer were as clear-cut as Beethoven’s. Neither was as committed an ideologue and, while Dallapiccola’s dramatic works reveal something of the radical politics of post-war Italy, egalitarianism shows up more as composerly technique rather than political statement. In twelve-tone music, each note is by definition equal to every other note—in essence the ultimate musical statement of Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité.

Perhaps there is a final reason for an interpolation such as the one we offer this afternoon. Our definition of the world has grown. The homogeneity of life experiences that one expected when the First Symphony was first heard some 219 years ago, when people rarely moved outside of the social circles, geography, income brackets, and ideologies of their births, has been replaced by an expectation of economic, ideological and geographical fluidity. The very notion that one can reinvent oneself and that that reinvention might not follow any pre-existing precepts, is one of the most important gifts of Enlightenment philosophy. On a small scale, that means that we are invited to create our private discontinuous interpolations—why, just last night I drove a German car to eat Thai food while wearing a French suit and did not feel any sense of psychic dissonance. Or, the invitation for re-invention and recombination might be grander: perhaps we don’t have to accept the precepts of earlier generations. We can choose anew how to live, whom to love, what problems to solve. And, whether small or grand, as I consider Beethoven—the revolutionary, the musical inventor, the shunner of emperors—I can’t help but think that he would have approved.

-Steven Schick