Guitar Faculty Richard Savino Builds a Future for Students Out of the Past

Students at SFCM get a long view of the guitar, from the instrument's early forebears to its 20th-century concert repertoire and contemporary masterworks.

Richard Savino is a walking history of the guitar—and quite a few of its predecessors.

The Historical Performance, Coaching and Excerpts, and Guitar faculty member arrived at his now-focus after a youth playing trumpet in his New York City high school marching band and singing in its choir, until a familiar incident in the lives of many guitarists: The Beatles' performance on The Ed Sullivan Show in February of 1964.

“I freaked out," Savino recalls with a laugh. "That was, for me, a totally unbelievable Big Bang moment." From the folk boom of the era into the guitar hero era of Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton, Savino stayed hooked, picking up an electric guitar and, while still in high school, playing in bands in places like the famed Bitter End in Manhattan. But after a few years in the debauched world of rock 'n' roll, he decided the scene wasn't for him. "We always sang Bach and Handel in my family, and I said, ‘I'm gonna study classical guitar now,’" he says. "But this was quite late: I was already like 18 or 19."

Savino adapted: He won a Carnegie Hall debut competition, and was—along with Guitar Department Chair David Tanenbaum—chosen to play in the first big masterclass Andrés Segovia ever gave in New York in 1982. (The pair didn't know each other at the time, though by strange coincidence, their fathers served in the same battalion in World War II.)

But having grown up playing in bands, Savino wasn't as drawn to the post-Segovia world of solo guitar, which Segovia purposely chose to push as an equal of the piano solo concert format. "I came at it as a more social endeavor, so I've always been insistent that my students are involved in playing music with other musicians, not just other guitar players," he says.

So Savino began gravitating to period instruments because of the multitude of ensemble settings available. "I like to collaborate, and playing in chamber groups demands a level of collaboration and communication that, to me, is at the heart of what makes music fun," an idea he says is "the first thing I tell my students."

Plus, he says, a reputation as a specialist opens a lot of doors. "If there's a Baroque concert and there isn't a keyboard available, if you've learned how to sight-read figured bass, well, that's your gig now." He remembers being called in at the last minute by Joyce DiDonato (whom he had worked with at the Santa Fe Opera) for a European tour after a visa issue with her guitarist. "She called me and said, ‘Can you prep all this in two days?’ And I said ‘yep.’"

Once you expand to pre-"modern" guitars, Savino says the instrument's repertoire expands to centuries from before the 16th century, a span only equaled by the organ. "I try to impart to my students that there is still so much repertoire to uncover and work on," he continues. "Don't get caught up playing the same concerto that everyone else plays. There are so many more composers and performers from the history of historical plucked stringed instruments that can really allow you to distinguish yourself."

The specificity of the field can also lead guitarists to unexpected places. Savino was recently tracked down by an art collector who'd seen him perform; the client turned out to own the largest private collection of Rembrandts in the world and the world's only privately-held Vermeer. Savino ended up working with the collector to create a series of 20 narrative videos, soundtracked by his playing, to accompany the collection as it's loaned out through the world. Adding to his passport, Savino was recently in Peru researching the composer Pedro Jimenez Abrill y Tirado, and will be returning to give a presentation about his work, a path he says more research-minded guitarists can follow as well, thanks to grants, scholarships and endowments.

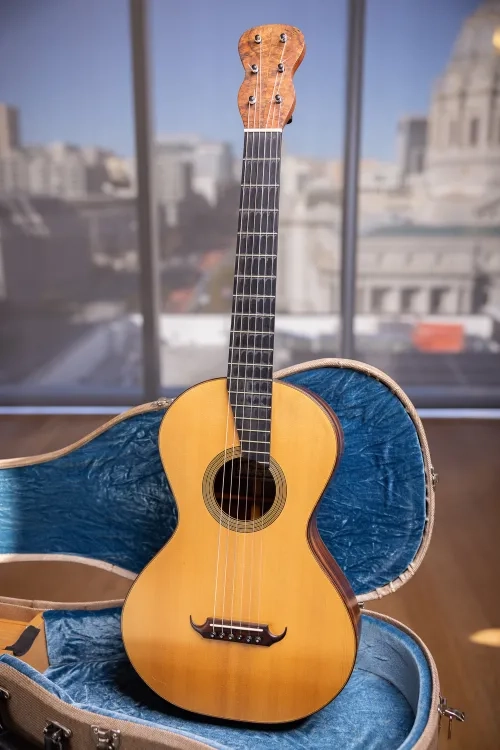

Savino has specialized on three historical guitars for nearly 30 years. One is a Baroque guitar that's a copy of a Stradivarius instrument. "Many people don't know that he made many guitars, but there are about five that exist," Savino explains. "One is dubious, and there are two that are very good, one of which I got to play when it was on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.”

The 12-string vihuela, he says, is often thought of as a guitar, but is actually a member of the viol family, tuned and played like a lute, but shaped like a guitar. On the opposite end of the scale is the theorbo, an oft-overlooked Italian lute in use until the early 19th century: "If you look at the payroll sheets of the Mozart Symphony Orchestra, they had chitarrone players on the payroll.” (Chitarrone, he explains, is simply a variation of the Italian word for guitar that translates to "large guitar.")

The third, six-string guitar is a copy of an early 19th-century guitar by luthier René François Lacôte. (There is currently an actual Lacôte for sale online for $21,000 if you're a stickler for authenticity.) This was an important period for guitar, because, as Savino explains, "That was when the guitar became codified as a six-single-string instrument after a period of constructions that often differed between countries. "It finally arrived at six strings for simplicity's sake," Savino says. "After all the double-stringed instruments, it was just less maintenance and less to tune. Because they're single, you can push the string harder and punctuate more. So that became the model, and then by the middle of the 19th century the modern classical guitar evolved in Spain.”

"These early guitars, in a way, gave birth to harmony," Savino says. "It’s the first documented instrument that had its own notational system for block chords, as opposed to harmony being the consequence of a linear overlap of voices." At SFCM, encouraging and working with guitarists who love ensemble playing, he's just carrying on that history of harmony.

Learn more about studying guitar or historical performance at SFCM.