How San Francisco's Asian-American Community Shaped 20th-Century Music

News StoryMusic History and Literature Professor Rachel Vandagriff maps the influence of San Francisco's AAPI communities on several of California's most iconic composers.

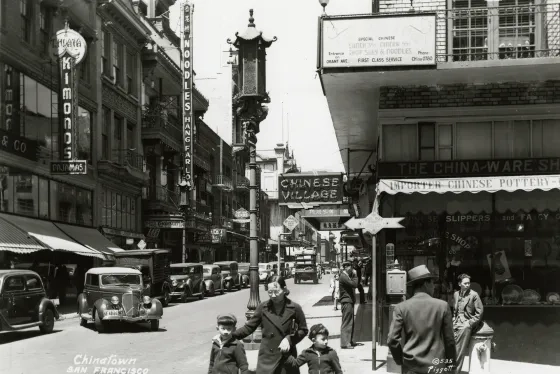

As the first "Chinatown" community in the United States, San Francisco's iconic neighborhood's historical status was secure from the get-go. Celebrating Asian-American Pacific Islander Month, SFCM outlines the community's importance on California's composers—and the Conservatory itself.

"In our Introduction to Music and Culture: Music in California, there are classes on Lou Harrison and Henry Cowell that speak to their absorption and interest in the music that they heard walking through Chinatown,” SFCM Music History and Literature professor Rachel Vandagriff says. “Both of them went to Chinese Opera performances, which was a very big part of San Francisco history and they were very inspired by the sounds that they heard." (Most of this would have been Cantonese opera; most of the Chinese immigrants who came to SF were from the Chinese province Guangdong, which includes the city of Canton. Peking-style opera is also frequently heard in the U.S.)

Cowell was born in Menlo Park and became a leading composer in 20th-century avant-garde music. He was raised in San Francisco by his mother and prior to the 1906 earthquake that devastated SF's Chinatown and would sit on the curb outside clubs and listen to music wafting out; he also learned songs from his Japanese, Chinese, Tahitian, and Filipino friends. Some of Cowell's experiments with tone clusters, like The Banshee, Aeolian Harp, and The Tides of Manaunaun, have joined the canon, and his piano technique was particularly influential to jazz pianists like Thelonious Monk, Cecil Taylor, and Don Pullen. Cowell's theory of "sliding tones," meanwhile, were definitely influenced by the vocal slides and non-fixed-pitch Chinese instruments he would have heard at opera performances.)

Lou Harrison was born in Portland, Oregon, though upon moving to San Francisco he studied with Cowell and similarly took influence from his visits to Chinatown. But he was more specifically interested in the Indonesian gamelan music he heard for the first time at The Golden Gate International Exposition in 1939, and strove to incorporate its pounding rhythms and non-Western scales into his compositions, particularly in 1971's “La Koro Sutro” (“The Heart Sutra”).

Another avant-garde figure of the 20th century, Harry Partch, had an even more direct claim to the influence of Chinese music than Harrison or Cowell: His parents were American missionaries in China and he claimed to have been conceived in the country. Partch was a musical maverick who often traveled across the country while developing a collection of self-made instruments that played in self-devised, non-Western scales. He attended performances at Chinatown's Mandarin Theatre after it reopened post-earthquake in 1924, referencing it in 1932's “On Hearing the Flute in the Yellow Crane House,” a setting of a text by Li Po in which he used the Chinese folk song “Mo Li Hua.”

Vandagriff adds that the music descendants of the AAPI community in California weren't strictly avant-garde figures, though. "There's an article by musicologist Mina Yang, where she talks about how Japan had only become Westernized in the middle of the 19th century, but Europeans had previously been there and established Western-style conservatories. So, many of the Japanese families that came to California wanted their children to play classical music, and orchestras were established.”

Vandagriff continues, “Yang traces that in an interesting way through how the first- and then second-generation immigrant kids adapt and absorb different music that their parents value, but also music that they get exposed to in America. That really resonates with so many of our students who are first- or second-generation immigrants."

And on a much closer-to-home note for the Conservatory, Ernest Bloch, the Swiss-American composer who was the director of SFCM from 1925 to 1930, was equally enamored of the music of Chinatown. The summer before his permanent move, Bloch was teaching a summer course, and a day after his arrival, was taken to lunch there and returned of his own volition, writing a letter to his wife of the experience, outlining the ensemble playing in a restaurant, "exactly like our Cantonese records."

After relocating to SF full time, Bloch spent much more time in Chinatown, writing in the program notes for his Four Episodes in Chamber Music that he attended Chinese opera performances "every evening for a whole week from 7 p.m. to midnight, fascinated by its music, its colors... all this fantastic imagination." In Episodes, Bloch quoted one of the melodies he'd heard during his weeklong intensive. Though one of his lesser-known pieces today, the suite won the Beebe Prize from the New York Chamber Society in 1927.

At SFCM today, there are multiple opportunities to explore the influence of the AAPI communities, both academically and musically. Roots, Jazz, and American Music faculty members Helen Sung and Akira Tana have both spoken about their experiences as first-generation immigrants, and in Tana's case, the history is especially poignant: His father, a Buddhist priest, was imprisoned in one of California's internment camps. Tana's group Otonawa bridges a musical gap between Japanese folk music and jazz, and have performed live at the Conservatory.

And most importantly, San Francisco's Chinatown is just a 20-minute MUNI ride from campus for those seeking to learn more about this historical community—and perhaps even forge their own musical tributes to it.

Learn more about studying music history and literature at SFCM.