Aldwell-Schachter Chapter 22

Click on a musical example for playback

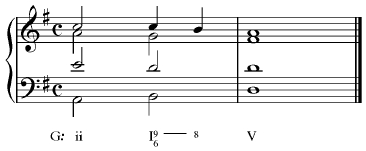

The development of a suspension: the soprano is delayed by one eighth note, creating a suspension on the second beat. Then the tenor is delayed the same way, producing a 9-8 suspension over the bass. Finally, the tenor is given an extra note which shows very clearly the nature of the cadential 6/4, as two accented passing tones (6 and 4) over the bass.

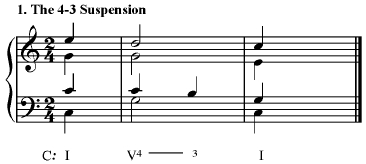

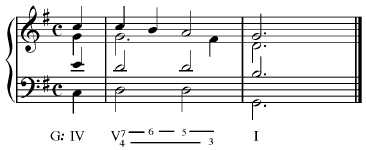

A typical 4-3 suspension in an inner voice. Such suspensions are among the most commonly encountered. Although the horizontal line connecting the tones of the suspension is not absolutely required, it’s a good practice to cultivate as improving legibility.

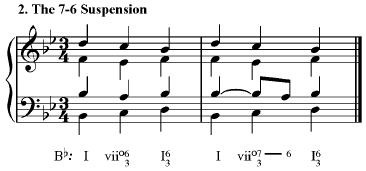

7-6 involves suspensions over inversions and thus one must be careful about the roman numeral analysis. Here a vii6 is suspended—it isn’t a ii7! When analyzing a suspension, be sure to look at the resolution of the suspension before forming any ideas about the root of the chord.

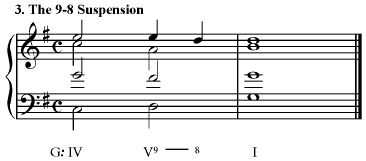

The 9-8 suspension is beautiful and generally offers little in the way of difficulty. Note that 9-8 is used, instead of 2-1.

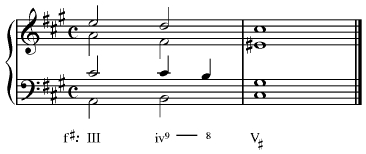

This is similar to the above example, with the 9-8 suspension in an inner voice.

The 9-8 suspension is by no means limited to root-position chords; any octave doubling can be suspended, after all, and therefore suspension is possible in inversions as well as root-position chords.

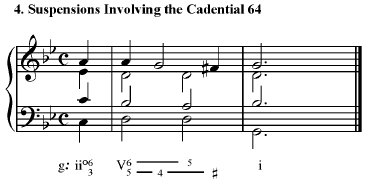

Here we have a “fancy” cadential 6/4. Note that it is necessary to analyze all of the resolutions—really waiting until the very last beat of the measure—before the root of the chord is clear.

Another “fancy” cadential 6/4, involving a 7-6 suspension in the soprano and a 4-3 in the alto.

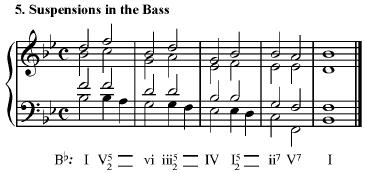

Bass suspensions can look confusing. Remember that the horizontal lines appearing below a note mean “nothing above the note changes”. To figure out the root of the chord, add ‘1’ to each of the figures before the horizontal lines—if the bass drops down by one step, each of the figures is increased by ‘1’, after all.

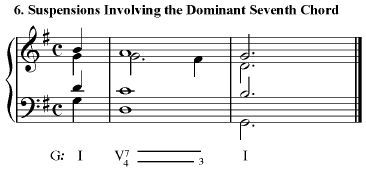

The 7th of the chord sustains through the entire measure; the horizontal line after the ‘7’ figure helps to show this. This is a second use of a horizontal line: to show the sustaining of a tone.

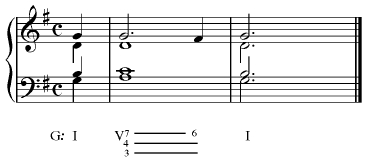

Another confusing-looking bass suspension. Here remember the horizontal line over a note in the bass means “nothing changes over this bass note”. So the figures, as of the 4th beat, are actually 6 & 5 & 3: this is a V6/5, in other words.

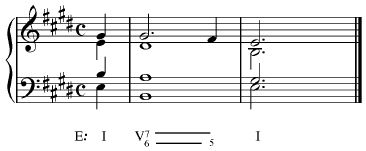

Here the 6th of a V4/3 is suspended. Note that the horizontal lines here are either indicating the connection (7-6) or just that a note is sustained (4 & 3).

Similar to above suspensions, the 5th is kept suspended as a 6th until the fourth beat of the measure. Examine the horizontal lines: the upper one indicates the sustaining of the 7th; the lower one shows the 6th connected to the 5th.

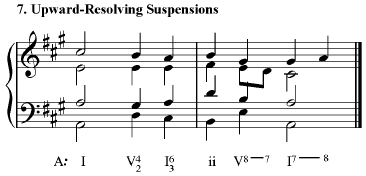

Although rare, suspensions can resolve upwards. Sometimes a 7th will resolve upwards to an 8th, as in this example.

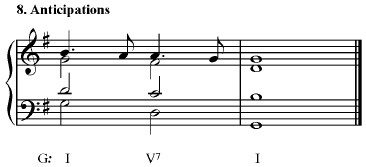

The anticipation can be thought of as an opposite of a suspension: instead of a chord tone coming “too late”, it comes “too soon.” Unlike the favored practice in analyzing suspensions, we usually don’t figure an anticipation—although it’s possible to do so.

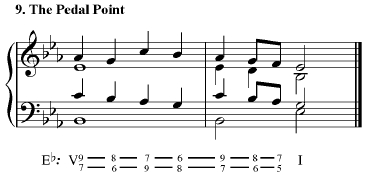

The pedal point (which can occur in any voice, here shown in its most typical position in the bass) is a technique of expanding a harmony by holding on to a single note and allowing the rest of the harmony to change around it. In this example the pedal point really is a vastly expanded V—sort of a super-cadential 64. There are other situations in which the pedal point must be removed from the progression before the chords can be accurately identified.