Sonata Form: Introduction

I. The Czerny-Marx Template

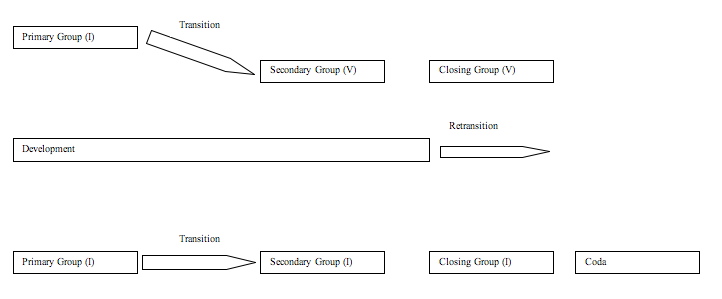

The description of sonata form developed by Carl Czerny and A.B. Marx in the 19th century is commonly encountered. The "Czerny-Marx" form can be diagrammed as follows:

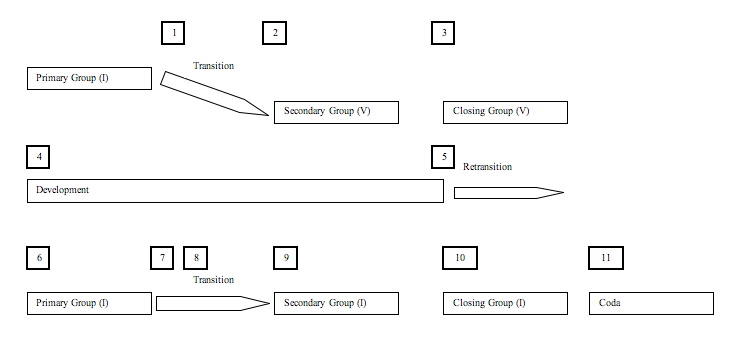

The Czerny-Marx 'template' describes sonata form primarily in terms of themes -- i.e., primary, secondary, and closing themes (or thematic groups), together with their development and eventual restatement. As a guide for composers to learn to write in sonata form, it's pretty good, but a quick examination of the musical literature -- especially sonata forms written during the latter 18th century -- reveals it to be a very poor fit. In the example below, 11 objections are raised to the Czerny-Marx template as an analytical paradigm; each is numbered on the diagram.

1. There may be no actual transition, but a bifocal close (half-cadence in the tonic key followed by material in the dominant key, usually the secondary theme proper. More information in the lecture on sonata form expositions.) instead. Conversely, the transition may explore a new key center (the so-called “three-key exposition.”) Transitions can sound like secondary groups, challenging the listener to distinguish between the two.

2. The “secondary” theme may be the same as the primary theme, or closely related. The actual point of arrival at the secondary group may be ambiguous, or there may be little harmonic stability in the secondary group not to be resolved until the arrival in the Closing Group.

3. There may be no closing theme or group; in other cases, the closing theme may resemble a ‘secondary’ theme, or be an altered restatement of a primary theme. The closing group may also lead directly into a transitional passage that either leads back to the beginning of the exposition, or forwards into the development.

4. The Development may include any of the following features:

It may have the same overall structure as an exposition

It may feature ‘false’ or ‘premature’ recapitulations.

It may not ‘develop’ at all, but may have freely-composed new material.

Finally, it may not even exist! (i.e., there may be no development at all.)

5. There may be no retransition, but a blurred distinction between development and recapitulation.

6. The recapitulation may skip the primary theme altogether, or if there are multiple primary themes, it may begin with 2P or later. The recapitulation may be relatively free in structure, not following the exposition or development.

7. The transition may be skipped altogether, depending upon the construction of the exposition.

8. The transition may give way to a ‘secondary development’.

9. The recapitulation may begin with the secondary group. In minor keys, the secondary group (and parts following) may be in the parallel major rather than the relative.

10. The closing theme may be a restatement of a primary theme, or may be so highly altered as to be unrecognizable.

11. Codas are not required; in many of Haydn’s mature works, it is virtually impossible to distinguish a coda from the main body of the recapitulation. It is also possible for the coda to occur within the recapitulation—especially immediately before the Closing Group.

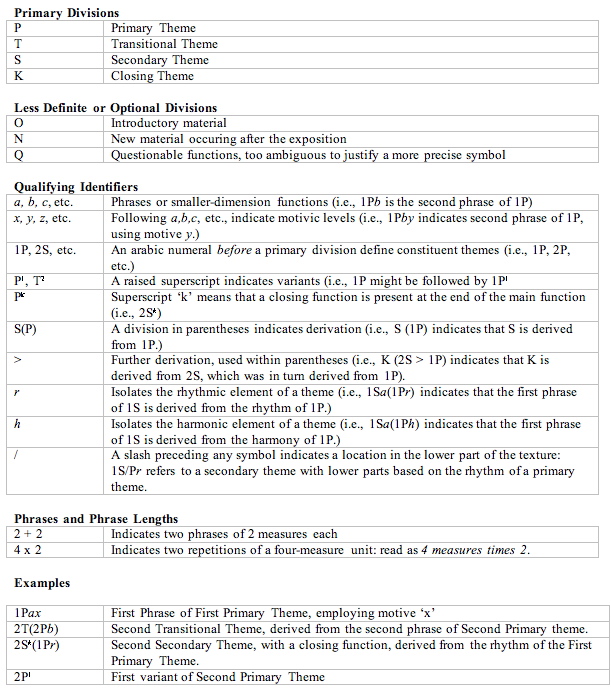

II. Jan LaRue's Symbols for Sonata-Form Analysis

Musicologist Jan LaRue developed a set of symbols which are commonly encountered in writings and discussions of sonata form. The system helps to identify materials within a sonata form in an economical, informative manner.

Here is a table of the symbols:

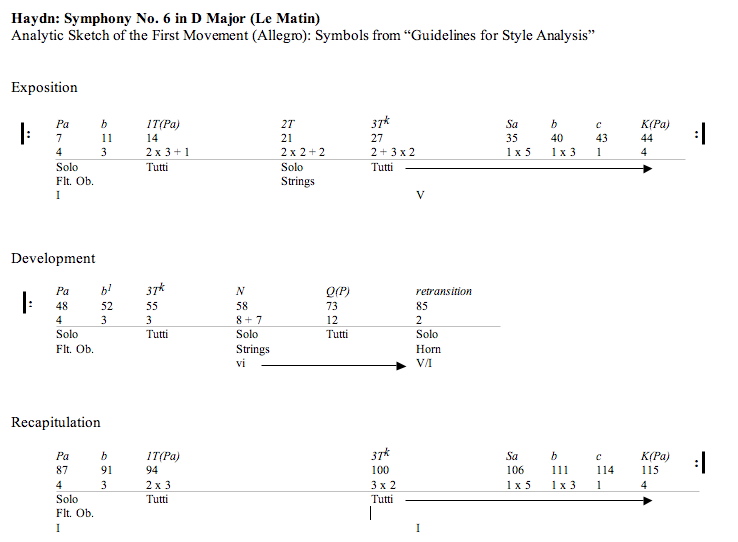

III. Sonata-Form Analysis Diagrams

The LaRue symbols may be used in everyday writing, but they come into their own most notably when they are used within a sonata-form analysis diagram. This diagram uses horizontal planes for each of the primary divisions of the sonata form (i.e., Exposition, Development, and Recapitulation, plus additional planes for introductions or codas as appropriate). The materials on the horizontal plane can vary, but at the very least each would include measure numbers and the LaRue symbols for the various components of the sonata form.

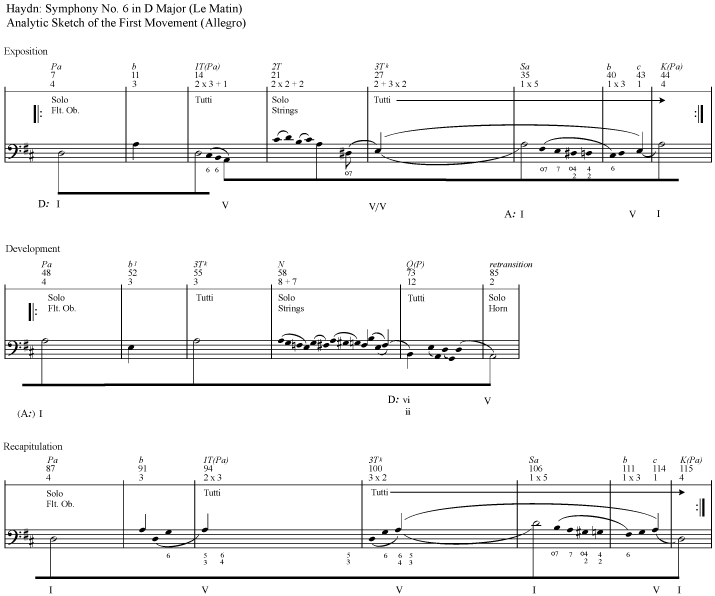

Here is a diagram of the first movement of Haydn's Symphony No. 6 ("Le Matin") first movement, omitting the short opening introduction:

To read the diagram:

Topmost row: the LaRue Symbols: 'Pa' means the first phrase of the Primary Theme, 'b' refers to the second phrase of the same theme, and so forth.

Second row: measure numbers

Third row: phrase lengths.

A horizontal line separates these materials for more optional materials:

Fourth row: instrumental details

Fifth row: harmonic analysis

It's strongly recommended that you listen to a recording of the Haydn symphony while following along with the chart.

It is also possible to create a more high-end version of the same diagram by including a reduction of the harmonic motion below the horizontal line of the diagram. Here's an example of that:

In many ways, the greatest difficulty in creating this kind of analysis diagram lies in the typesetting (it has been created entirely in Sibelius, rather than using a word processor.) However, it provides a great deal of information in a very small space.