Period Expansions

I.Extensions of Phrases Within a Period: Hear Scott Foglesong's lecture on this section.

A.Extension at beginning of phrases

1.Typically such an extension will be of an introductory nature. However, one must be careful to distinguish between an actual full introduction (which will be at least a full phrase in its own right) with an expansion at the beginning of another phrase.

2.Schumann’s Widnung gives an example of a single-measure introduction at the beginning of the period. Click on the musical examples to hear playback.

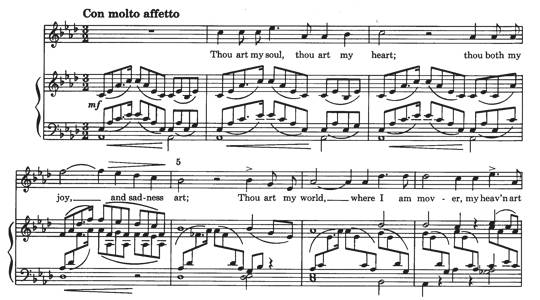

3.Although rare, extensions to the beginning of both antecedent and consequent do occur. It is very difficult to maintain the cohesion of the period under such circumstances, but by keeping the ‘introductory’ nature of the extensions firmly under control—and keeping them similar, it is possible. This extract from a Schubert lied shows how it can be done. Note that the expansions are piano alone, while the main body of the period is voice with piano accompaniment.

B. Extension at end of phrases

1.Haydn Minuet: a long and clear expansion to the cadence of the consequent, introduced by an evaded cadence. (Although technically the extension stands between the evaded cadence and the actual cadence at the end, the extension really is to the end of the phrase, and not ‘within’ the phrase—it’s the ending, or cadence, of the phrase which is being extended.<

2.Mendelssohn Song Without Words No. 31, with a repeated 4-bar period which is then expanded almost identically to the Haydn above.

C.Extension within phrases

1.This Haydn ililustrates a period with a two-measure extension at the end of the antecedent, and a two-measure extension within the consequent.

2.This Mendelssohn is a clear example of an expansion within the consequent. It might be possible to analyze this as an expansion at the end of the phrase (and in fact one analysis text does just that), but harmonically an analysis of the extension at this spot makes more sense. Besides, the passage in smaller typesoundslike an interpolation.

II.Repetitions: Hear Scott Foglesong's lecture on this section.

A.Repetition of antecedent alone. It is relatively rare, all things considered.

B.Be careful not to confuse this with AAB forms in which the first phrase is repeated; in most cases, the two phrases A & B aren’t in a periodic relationship with each other. (That’s the case with the 12-bar blues, for example, or the bar form of the medieval Minnesingers of Germany.) Both the 12-bar blues and bar form are examples of simple two-part song form, and aren’t periods.

C.Here are a few examples of periods with repeated antecedents only:

1.Beethoven String Quartet Op 18, No 3: III. At the beginning of the “minore” section:

2.Shostakovitch: Three Fantastic Dances Op 11, #3. Note how the consequent is almost like a 2-measure phrase with an immediate repetition. Such a structure helps ameliorate the sense of imbalance created by the lack of repetition in the consequent.

D. Repetition of consequent (either exact or with slight modifications)

1.Mendelssohn Song Without Words #14

2.Beethoven Piano Sonata Op 10 No 1: II

E.Repetition of both antecedent and consequent

1.Note that Berry’s example on page 21 of the textbook is more likely a double period (or even a two-part song form) rather than antecedents and consequents with repetitions.

2.In this Mozart, note that the consequent’s final repetition is slightly modified:

3.In the Mendelssohn example below, note the expansion of the consequent, followed by a fairly substantial modification in the repetition:

4.Take care not to confuse this structure with that of a double period (A A’ B B’) which is relatively common.

F.Repetition of entire period

1.Period with a repeat sign—no examples are needed; they abound!

2.Written out, possibly a bit modified:

3.With changes of instrumental color: consider Haydn’s penchant for adding flutes to a repeat, for example.

III.Phrase Group: 2 or more phrases NOT constituting a period: Hear Scott Foglesong's lecture on this section

A.A A’ A’’: in this Mendelssohn example, one might be tempted to think of this as being a period with a repeated consequent. However, in this example, note that it is not reducible to an identifiable period. This example is a phrase with two (varied) repetitions.

B.A B C: the easiest kind of phrase group to spot is one in which all three phrases are quite dissimilar. This Mozart piece suffices to demonstrate what is encountered quite frequently in music of all periods:

C.A A’ B: what makes this a phrase group, and not a period with a repeated antecedent?

D.Why is this a phrase group A A’ A’’ and not a period with an expansion?

IV.Chain Phrase: Hear Scott Foglesong's lecture on this section and the next.

A.“Chain phrases” consist of sub-phrases (usually two measures or less) found within a sequential passage, bound together into longer units. They are similar to phrase groups, but the four-measure unit is difficult to find.

B.The term chain phrase is by no means universal, but it’s a useful term for a common phenomenon.

C.Chain phrases are often found in modulatory sections, typically sequential. The small units tend to gather into larger units, which remind us of phrase groups.

D.Here’s an example from Mozart’s F Major Sonata, K. 332. Note how the chain phrase begins with two 2-measure units, and then becomes a series of 1-measure units. Harmonically the sequence is an ascending fifths sequence (c-g-d-a) expanded by inversions and applied vii7 chords.

V.Double Period

A.Definitions:

1.Four phrases in coherent succession, generally with HC at the end of the 2nd phrase and AC at the end of the 4th phrase.

2.Goetchius: The Double period consists in the union of two periods, an embraces, consequently (when regular) four Phrases, so conceived and distributed that the Period-relation is apparent between Phrases 1 and 2, between Phrases 3 and 4, and also, on a broader scale, between these two pairs. The two Periods of a legitimate Double-period form are just as coherent, and just as closely dependent one upon the other, as the Antecedent and Consequent Phrases of the simple Period forms are. And for this reason, the Cadence in the center (i.e., at the end of the 2nd Phrase) must be in the nature of a Semicadence, though almost unavoidably somewhat heavier than an ordinary light semicadence.

B.Examples of the parallel double period

1.Beethoven Sonata Op. 26

2. In the Berry text, example 1.43 (page 22) is a standard parallel double period, similar to the above example.

3. Also in the Berry text, example 1.44 (page 23) displays a parallel double period with the final consequent being significantly expanded by sequential development.

C.The “contrasting” double period is really a two-part song form. Some analysis texts attempt to make a distinction between the two, usually with near-disastrous results. It is best to restrict the term “double period” to those examples which display the kind of structure as the examples above—i.e., those which display clear parallelism between the first and second periods, and a clear half-cadence at the end of the first period. Otherwise, it is best to refer to such forms as “two-part song form” or even “simple binary”. (We’ll be covering those soon.)