Phrases

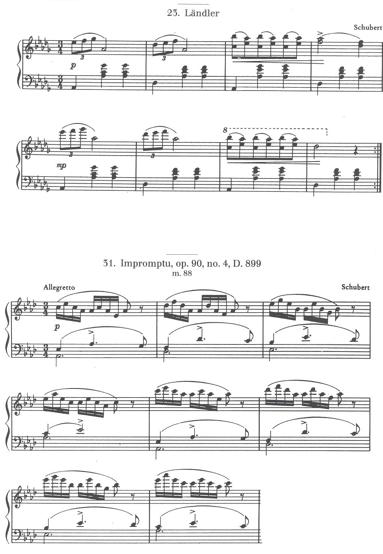

Click on the musical examples for playback

I. Conventional phrase: four measures long, terminated by a cadence, usually authentic or half. The idea of the conventional 4-bar phrase is a convenient starting point for study, and is not to be taken as some kind of holy writ that all phrases are four measures long.

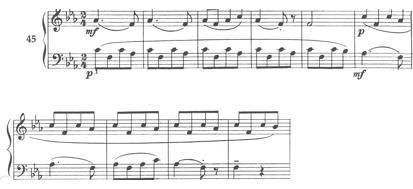

A. Conventional phrase ending in an authentic cadence

B. Conventional phrase ending in a half cadence (first four measures) followed by a second phrase ending on an authentic cadence.

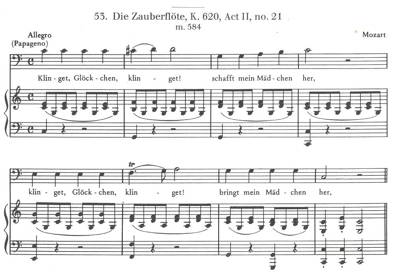

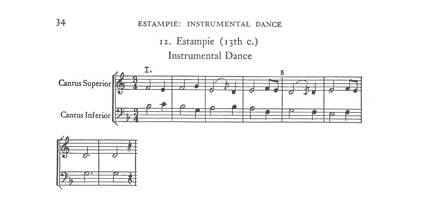

C. Conventional phrases are found in early hymns, troubadour songs, dances, and so forth. The example below shows an early Estampie.

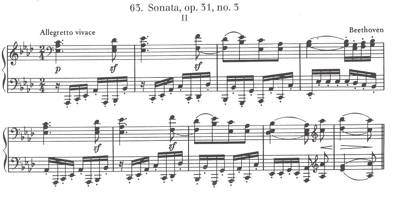

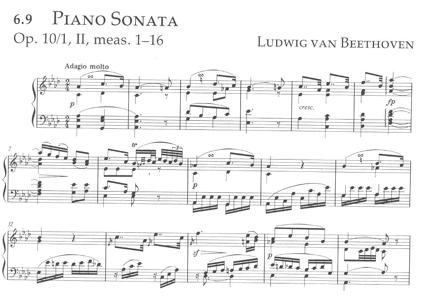

D. The notation may mask the four measures sometimes. When the tempo is slow or the measures large, the phrase may extend through only two measures. Conversely, in rapid tempi or short measures, the phrase may contain eight measures. The example below shows a four-measure phrase which is written as eight measures: the implied meter is probably 6/4, given the fast tempo.

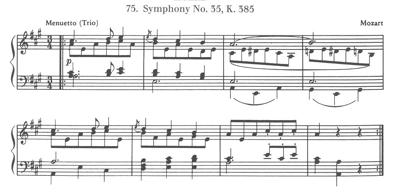

E. The phrase is typically divided into semiphrases, usually two measures long. These will in turn further subdivide into motives and their manipulations. The Mozart G-minor Symphony theme –4[2+2] gives an example, with the subdivisions being all motivic. While the phrase may subdivide, there is absolutely no rule that it must.

F. Counting measure numbers with upbeats: begin counting measures with the first full measure (no matter how long the upbeat may be) and end with the last incomplete measure, no matter how short it may be.

II. The Phrase as Shortest Unit Terminated by a Cadence

A. The semiphrase is distinct from the phrase by virtue of the phrase’s ending with a cadence.

B. A 2+2 phrase may often seem to have a cadence at midpoint, but it’s a cadential inflection (some kind of pause) and not a real ending. Consider the opening of Richard III

Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this son of York.

which illustrates the semiphrase (first line) nicely. The end of the line is a pause, not a punctuation—the sentence is actually meaningless until it is completed by the second line.

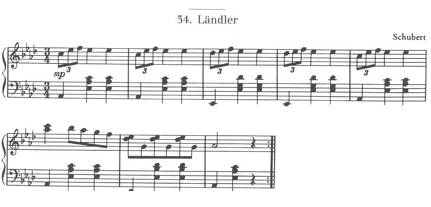

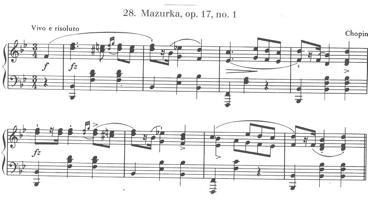

1.The Chopin Mazurka below: one could opine a plagal cadence in measure 2, but measures 3-4 provide a solid V7-I cadence. Remember not to interpret every V-I as an authentic cadence and every IV-I as a plagal cadence: madness lies in that direction.

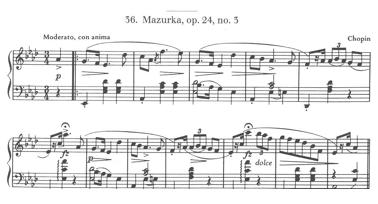

2.Another Chopin Mazurka. Measures 1-3 form a phrase V7-I-V7-I. However, we don’t hear measure 2 as an authentic cadence due to the melodic notation—which pulls us forward into the next measures, and introduces a distinct non-chord tone into the proceedings. The moral here is to consider everything in your analysis, and not just the chords.

III.The Phrase as a Component of a Larger Pattern (more on this in a few weeks)

A.Sentence (period) of two phrases.

B.Double period consisting of four phrases.

C.Phrase group consisting of three or more phrases.

IV.The Phrase as Independent Unit

A.A phrase can be isolated, not apparently associated with the preceeding or succeeding phrase. Thus a phrase can act as a prelude, postlude, coda, interlude, or even a transitory passage.

B.It’s important to be careful before identifying a phrase as independent!

V.Repetitions of Phrases

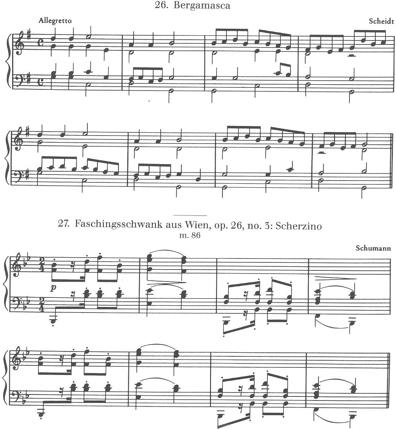

A.Identical

B.Embellished

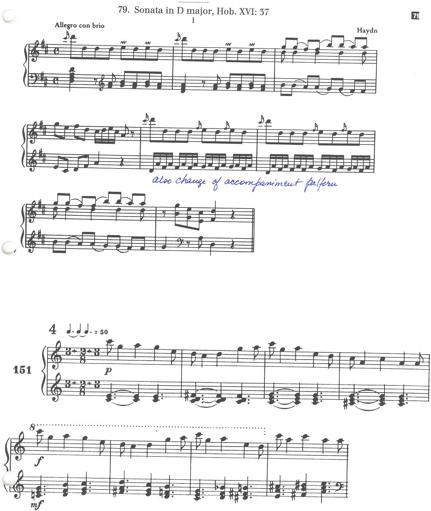

C.Harmonic Changes

D.Accompaniment Changes

E.Register Change

F.Color (orchestration) change