Aldwell-Schachter Chapter 10

Click on a musical example for playback

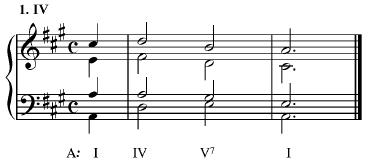

IV preparing V. Note that the soprano is moving in contrary motion to the bass; this particular soprano motion of ^4-^2-^1 is one of the more characteristic progressions found in cadences. Care must be taken with the voice-leading of IV to V, since the two chords share no tones in common.

Here, the soprano ^1-^7-^1 is also characteristic at cadences. Note that I have selected a voicing for IV which results in a unison doubling in the following V7; this is not illegal or even uncommon.

This soprano, ^6-^5-^5, prepared by ^5 in the soprano supported by I, would not be particularly typical for a final cadence (^5 in the soprano is relatively unsatisfying) but is a fairly typically encountered progression. I and IV share a common tone and thus I is commonly encountered as a preparation for IV. Also note that minor mode does not pose any special difficulty.

Generally speaking contrary motion in the outer voices is your best bet for IV-V. It isn't absolutely required; here I have set a IV-V progression using parallel motion in the outer voices. Note that I had to resort to a rather awkward leap in the tenor, however, in order to avoid problems.

However, this most emphatically will NOT work in minor: the progression ^6-^7-^1 in the soprano is applicable in major, and in major only. Otherwise you will wind up with an augmented second. To make this work in minor, it will be necessary to raise ^6, and create a major IV—and then it will work just fine.

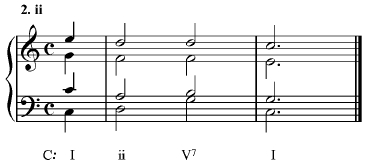

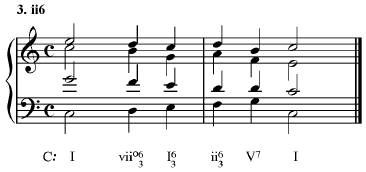

The supertonic ii shares ^2 with V, as well as ^4 with V7. This makes it quite adept at motion to V as well as V7. This first example shows ^2-^2-^1 motion in the soprano.

Here the motion in the soprano is ^4-^2-^1, again quite typical. Note that in approaching ii from I (as in this and the preceding example) you must move in contrary motion between the outer voices to avoid parallels.

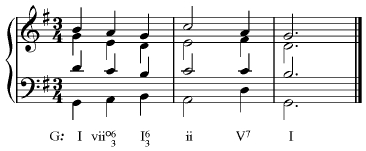

Another typical soprano motion: ^2-^7-^1.

You might be inclined to think that because we have seen so much motion from I to ii in these examples, that you could slip 'ii' in as a substitute for vii6, or V43, in the first measure of this example. This is not permissible. It is not only illegal, but it is also illiterate. II does not function as a passing chord: it leads to V, and to use it in this context is harmonic sabotage.

Another thing you should not do is to use ii in minor. Because it is a root position diminished chord, it has a very unsatisfactory, ill-humored sound about it. Although there might be some situations in which it is allowable, for now think of it as a forbidden sonority.

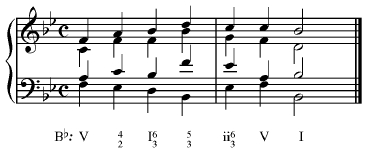

ii6 shares a common tone with V (unlike IV) and therefore makes an excellent preparation for V, without as many voice-leading problems as can beset a IV-V motion. That isn’t to say ii6 is a voice-leading garden party; it carries its own dangers.

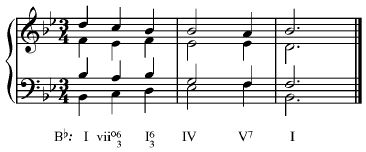

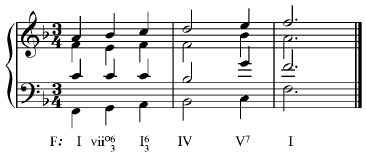

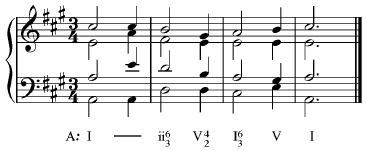

Both ^2-^7-^1 and ^2-^2-^1 are commonly encountered soprano figures set with ii6. Note in this example that I have doubled the bass note of the ii6; this is quite common, probably as common (or more common) than doubling the root.

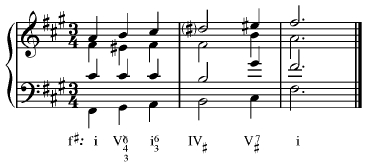

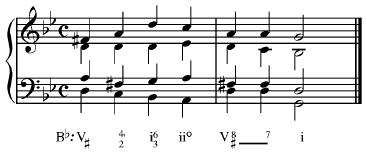

Although ii6 can be used in minor mode quite comfortably (unlike root position ii), you must be careful about the augmented second that lurks in the voice-leading (just as you have to do with iv.) Here is an example in which the augmented second has appeared.

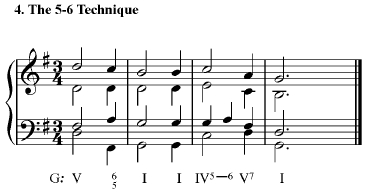

This idea comes from the notion that IV and ii6 are almost the same chord. Moving the 5th of IV to a 6th creates a ii6, in fact. So it can be argued that a figure such as the one in measure 32 is really IV5-6 in that there is no real change of root. You may also analyze this as IV-ii6, but the analysis of IV5-6 is really much more cognizant of the actual harmonic progression that the ear hears.