Aldwell-Schachter Chapter 25

Click on a musical example for playback

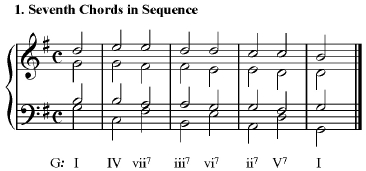

In a chain of interlocking seventh chords, the 3rd of one chord becomes the 7th of another. Because the 7th of the seventh chord must resolve downwards and by step, in four-part writing every other seventh chord will be incomplete.

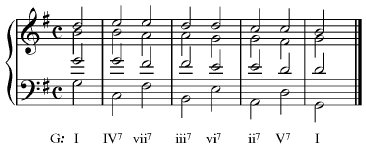

This is the same progression, voiced a bit differently, but still demonstrating the need for every other seventh chord to be incomplete.

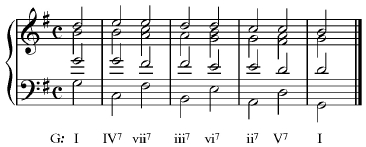

A free texture (or a five-voice texture throughout) is required to achieve complete seventh chords through the progression.

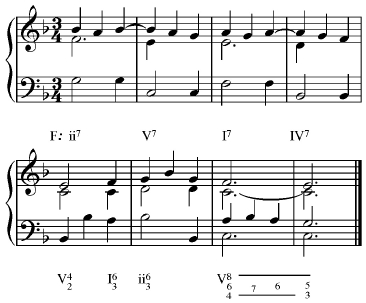

These interlocked seventh chord sequences lend themselves to a lot of elaboration—just like their non-seventh-chord counterparts. This is a simple example in a free keyboard texture that could very well be part of a period phrase in a rococo or early classical period minuet.

The seventh chords do not have to be constant: you can alternate 53 triads with seventh chords perfectly well, as long as you respect the downward resolution of the seventh chord.

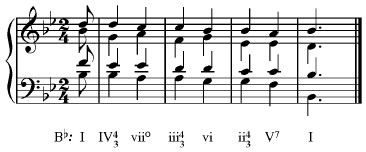

There are numerous possibilities for descending fifth sequences incorporating inversions of seventh chords, either with or without triads. This is one of many: 43 chords alternating with root-position triads.

It stands to reason that a descending fifth sequence is not the only sequence capable of sustaining seventh chords. Here is an example of a descending thirds sequence with a seventh chord every other chord.

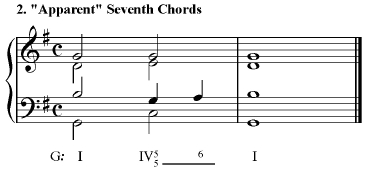

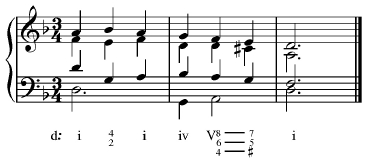

The notion of the ‘apparent’ seventh chord can be seen clearly here: there is a simple passing note in the tenor which produces what looks at first glance to be a ii65, but in reality we hear it clearly enough as a IV with a passing tone. This is conceptually very similar to the “5-6 Technique” in that the ear interprets the motion, and doesn’t insist on changing the root of the chord on the fourth beat.

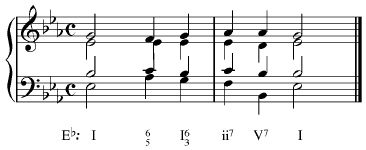

This example is a less textbook-ish use of the apparent ii65. In any number of compositions such a progression is perfectly possible, in a lot of periods. Although we would tend to associate it more with Romantics like Chopin, it is used prior to that era as well. Note that in this and later examples, the apparent chord is analyzed as figures only, without a root.

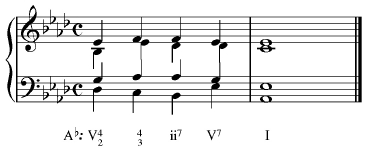

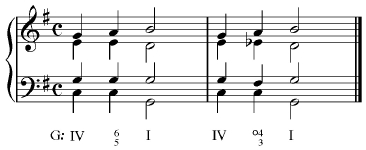

In a similar manner to the above, a 63 chord can be turned into an apparent 43 by the addition of a fourth above the bass note. In actuality, this is a I63, and the early certainly hears it that way—note that there is no disturbance over the fact that it is being used to resolve a V42, which is predisposed towards resolution to a I63.

With the bass stationary, the contrapuntal motion produces what seems to be a ii42 on the second beat. This is not really any such thing, and in fact acts rather like a neighboring iv64.

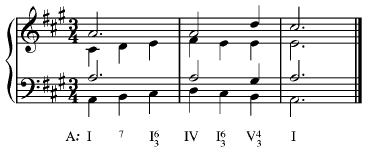

This is a variant on the apparent ii65 that was discussed earlier. With the change of the notes in the inner voices, the apparent ii65 in measure 1 becomes an apparent vii43 in measure 2—but nonetheless the ear hears it comfortably as a IV.

Soprano-voice pedal points can produce some interesting apparent seventh chords as well: note that the second beat of the first measure appears to be a ii7, but it’s really nothing more than a vii6 with a pedal point in the soprano; this produces the ‘seventh’. The ear isn’t bothered; we hear it for what it is.