Aldwell-Schachter Chapter 11

Click on a musical example for playback

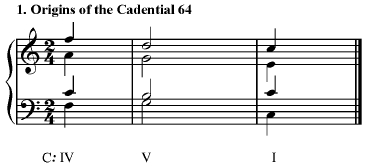

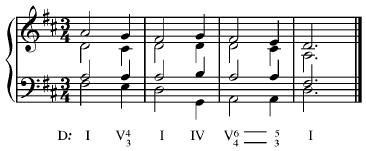

How to create a cadential 64: the first step is a dominant on a strong beat, as in this example.

An old voice-leading practice involved “suspending” the 5th of IV (which is ^1), and not resolving it until the next beat, to ^3.

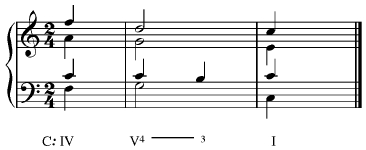

Adding a passing tone in the soprano, filling in the jump between ^4 and ^2 in the previous example, creates an “accented passing tone” ^6-^5 which has much the same stress and power as a suspension.

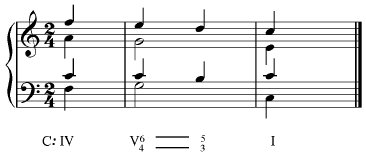

This figure becomes the cadential 64, which should be analyzed as V6/4-5/3, and not with the first chord as I6/4.

This example may help dramatize when analyzing a cadential 64 as “I6/4” is inappropriate. Consider the very different effect of ^1 as it appears in the soprano of this exercise—especially the difference between the downbeat of measure 2 and the downbeat of measure 3. In measure 2, ^1 is dissonant to the bass and therefore does not sound like a goal; it is not a rest tone. In measure 3, ^1 is the goal of motion, a rest tone. In a tonic triad, ^1 acts as the ultimate rest tone, the ultimate goal of motion. But that is not the case with a cadential 64, which is clearly an expansion and intensification of the dominant, not the tonic.

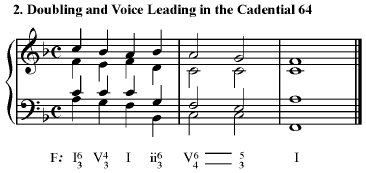

It is generally best to double the root (bass note) of the cadential 64; most of the time that’s what you do, so you almost don’t have to think about it.

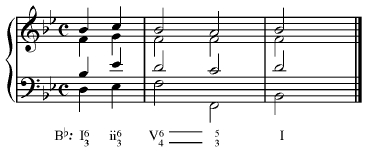

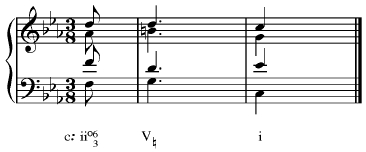

One should not be slavish about doubling the bass note of a cadential 64, however. Such slavish adherence to the principle will result in the situation outlined here, in which there are parallel fifths moving from ii6 to the cadential 64.

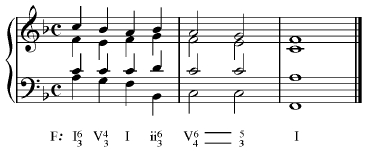

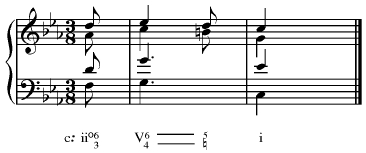

Here’s the first (and most conventional) solution to the problem: since it is the motion from ii6 that is causing the parallel, change the voicing of the ii6. Here I’ve arranged the voicing so that the parallel fifths become parallel fourths, which are perfectly legal. Note that this meant changing the following cadential 64 as well—rewriting the inner voicings. Unless the circumstances are truly compelling, this is the strategy to follow.

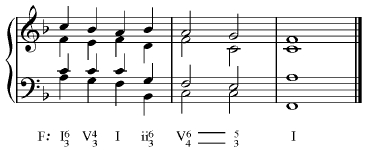

This solution is a bit more arcane but marginally acceptable: change the voicing of the cadential 64 and double the sixth above the bass instead of the bass. This is not the best practice and so not recommended; normally we would move the 6th above the bass to the 5th, which is happening in the soprano, but not in the alto.

This might look like a solution on paper, but it’s not at all acceptable. Doubling the 4th of a cadential 64 is an extremely dubious practice, unless the texture is extremely free. The 4th above the bass is so sharply dissonant that it must be resolved downwards, and the leap that necessitates for one of the notes forming the 4th (to avoid parallel octaves) is wholly unsatisfactory.

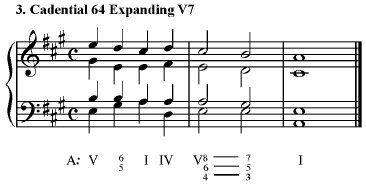

When the root (bass note) of the cadential 64 has been doubled, it is perfectly possible to move that root down a step to form a seventh over the bass, and thus allow the cadential 64 to prepare a V7 instead of a plain old V. This construction is common. Note that the V7 behaves precisely like any other V7; here I invoke Bach’s practice and allow ^7 to leap down to ^5.

Sometimes the voice leading in the cadential 64 might result in a slightly different motion to V7. It is the 6th of the cadential 64 here that moves to 7, and not the bass doubling. Thus the V7 is incomplete—paving the way for a complete I. Although the “real” figures are notated below the bass, it is acceptable to use the more familiar cadential 64 analysis (as in the example above) instead. The more precise analysis is recommended, however.

Along similar lines, this example moves to a V7 after having doubled the sixth above the bass. Note that one of the 6ths moves upwards to form the 7th, while the other moves downwards to form the 5th. This results in a complete V7, and thus an incomplete I.

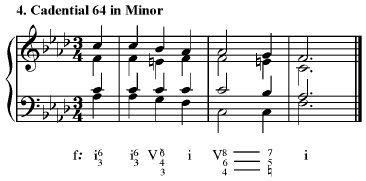

There is little to worry about in minor except that the 3rd of the V has been raised and must be indicated as such in your figures, just as would be the case with any kind of dominant.

However, a strategically placed cadential 64 in minor could help you in overcoming a typical problem with an augmented 2nd, given that the 4th of the cadential 64 delays the leading tone and therefore can serve to remove the offending interval. This example shows an exposed augmented second moving from the pickup to the downbeat.

Here, the cadential 64 has served to ameliorate the problem of the augmented 2nd.

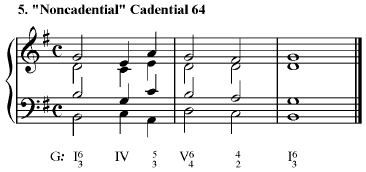

It would seem that Aldwell-Schachter had been reading The Diamond Sutra prior to coming up with this term, one of their finest examples of mangled English. The usage here involves moving the cadential 64 downwards to a V4/2 instead of a V; the bass line moves downwards by step.

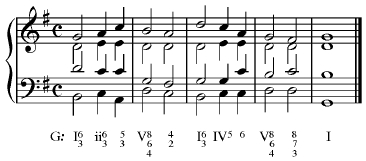

Judging from the above example, it seems clear that the “noncadential cadential 64” is a good technique to use in expanding a phrase—by delaying the final cadence. Here’s a way to write a double cadence of the sort that might be favored by later 18th century composers. (The practice stems from the need to make the structural divisions of a composition clear to listeners on limited hearings, given the populist nature of much Classical era music.)