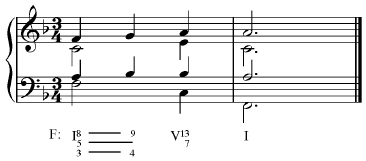

Aldwell-Schachter Chapter 28

Click on a musical example for playback

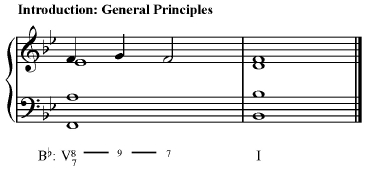

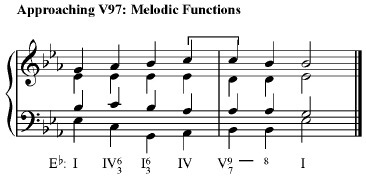

Starting out simply, we see here a V7 which has been decorated with an upper neighbor tone before resolving normally.

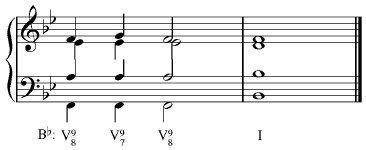

If we repeat the bass notes in the first measure, it’s easier to see that the chord on the second beat looks (and sounds) rather like a chord with an added ninth above the bass—a V9/7. Note that the chord is spelled as an incomplete V7 with an added ninth—thus it is almost always written as V9/7.

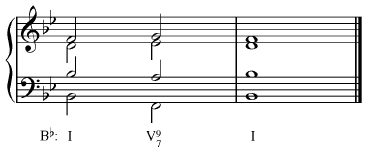

Extending the idea yet farther, I see that I can use the V9/7 without actually resolving it to a V7—and thus the 7th and the 9th resolve downwards, by parallel motion.

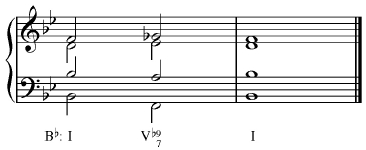

Because a modally-mixed ^6 is so common, the V9/7 can be mixed very easily.

An approach to V9/7 from IV can be quite effective, by maintaining the common tone (the 3rd of IV becomes the 9th of V9/7.)

This approach from ii6—showing the same common tone—also demonstrates that the 9th does not have to be in the soprano, although that is the most common location.

This isn’t particularly common but it’s perfect OK. The 9th is treated as a descending passing tone from natural 7 to 6 to 5. Note that this creates a cross-relation between the soprano and alto, but due to the chromatic motion in the alto line, it is not objectionable.

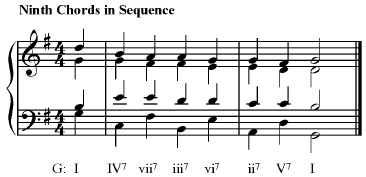

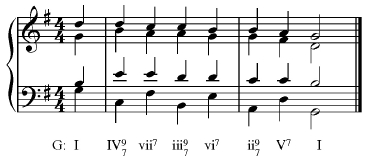

This is a descending fifths sequence in seventh chords.

You can use 9/7 chords with such a sequence, but only on every other chord: attempts to create ninth chords throughout will require an extra voice; this isn’t impossible by any means, but would not be the norm in a strict chorale style.

The expressive power of such a sequence is here demonstrated in this (arranged) excerpt from Brahms 3rd symphony; note that it starts with a IV9/7, and thereafter does not use ninth chords, but the sheer power of the ninth chord is such that the ghost of the possible ninths (notes in parentheses) remains in force throughout.

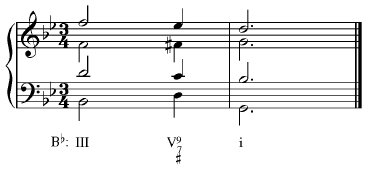

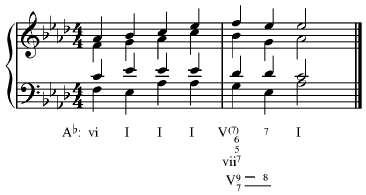

The relationship between V9/7 and vii7 is very close; in fact, V9/7 is almost a vii7 (half-diminished) with the root omitted. The relationship is close enough so as to blur the distinction between an ‘inversion’ of V9/7 and a vii7—or maybe this should be thought of as a V7 with a 9-8 suspension, and a motion in the bass.

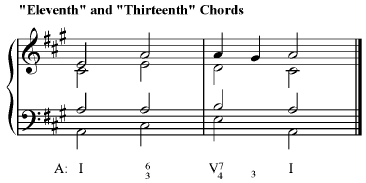

So far, this is perfectly familiar: a dominant seventh with a 4-3 suspension in the soprano. But what happens if the suspension doesn’t actually resolve?

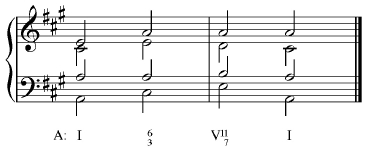

Immediately we recognize that this would not be something we might hear in 18th century music—but it just might be heard in the 19th century or later. Although it really is a V7 with an unresolved 4-3 suspension, sometimes it gets called an “eleventh” chord (because the dissonant note is an 11th above the bass.)

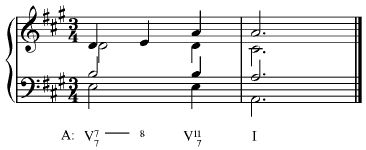

For example, this is a sketch of part of Stephen Sondheim’s song, “Send in the Clowns”. In pop and jazz circles, the idea of the eleventh chord is firmly ensconced; we hear the function of the first measure clearly as a dominant—which seems to resolve in the second measure, but we aren’t particularly bothered by the apparent non-resolution of the 11th.

Much along the same lines, we might allow an unresolved 6-5 suspension over a dominant, which produces a “thirteenth” chord.