Aldwell-Schachter Chapter 18

Click on a musical example for playback

The essential nature of the sequence is demonstrated here: an expansion device that allows motion, allows repetition, but does not require immediate resolution.

Sequences consist of a pattern which is repeated a number of times: an instance of the pattern is an iteration of the pattern. Generally speaking three iterations is the maximum unless the pattern is extremely short and simple.

A sequence is called melodic if the repetition occurs in the melody only, and harmonic (or polyphonic) if similar repetitions occur in all of the parts. If the repetitions are made without accidentals, the sequence is called tonal or diatonic. If, on the other hand, the intervals of the model are preserved exactly, the sequence is real. In practice most real sequences are slightly altered, and are called modulatory or chromatic sequences. For the time being, we concentrate only on diatonic sequences using 53 and 63 chords.

In most tonal music, a melodic sequence implies a harmonic sequence, and vice-versa. It is generally not a good practice to set a melodic sequence non-sequentially, given that the ear picks up on the sequential pattern in the melody and is disturbed by the lack of harmonic consistency with the perceived melody. Thus it is also generally a good idea to set a harmonic sequence with melodic sequences—retaining similar voice-leading throughout, in order to avoid the same kind of confusion.

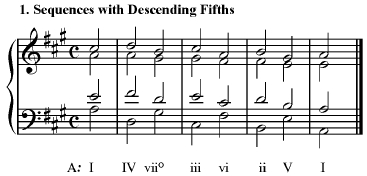

This is a typical descending fifths

sequence. Note that all of the voices are sequential. The complete sequence from I-I is given here, although a portion of the sequence can be used.

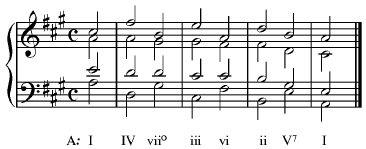

This is the same sequence, although with a changed soprano to show a variant. One important thing to notice here is that the iterations are not completely dogmatic: for the final cadence the soprano motion has been changed to ^2-^1, rather than ^7-^1 as it would have been otherwise.

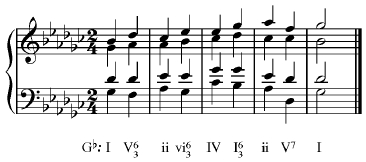

The same sequence as above, but in minor. There is one important modification: ii on the downbeat of measure 3 has been changed to ii7, in order to avoid the barren sound of a ii in minor. Other than that, the progression works just fine in minor (and you could use the root-position diminished ii if you wanted—although the ii7 is a much more attractive sonority.)

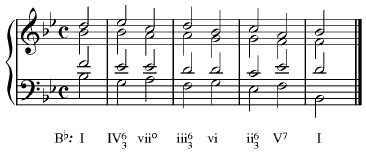

This is also a descending fifths sequence, but every other chord in the pattern has been changed to a 63. This allows a less jumpy bass line, and some contrast from the unending chain of root-position chords.

Here the descending fifths alternates 53 and 63 chords with the first chord in the pattern changed to a 63. This makes for an ascending bass line, at least during the pattern, rather than the descending pattern one would ordinarily expect from a sequence called descending. This highlights the necessity of considering the roots of the chords when you are an analyzing a sequence.

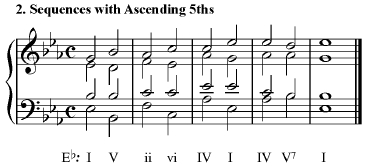

This is a basic sequence in ascending fifths. The most important aspect here is that skipped iteration—the third one that would have moved III-vii. This landing on vii would create a very unpleasant sonority, and would also leave the progression without any clear direction.

This is a sequence in minor. Like its counterpoint in major, it has skipped an iteration. Also note that it has not begun on I, as did its major counterpart, but on III. Beginning on I doesn’t work well, although skipping the iteration on ii and moving directly to III can work.

A more plausible version of the above sequence. Moving the sequence through the third iteration is a bit artificial sounding; limiting it to two iterations alone and then moving to a cadence is much more convincing.

This variant involves a 63 triad for the second chord in the pattern. Note that the third step of the iteration (iii-vii) has been skipped. There is a Chopin example on page 272 of the 3rd edition of the textbook (example 17-8) which incorporates applied dominants but is otherwise this same progression.

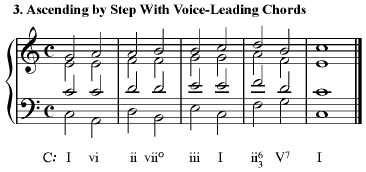

This technique involves using a stepwise motion that would normally result in parallels, but interposing voice-leading corrective chords—in this case, the chord a third below

.

Using a different voice-leading chord (in this case, a chord a fifth below rather than a third) creates a very satisfying effect.

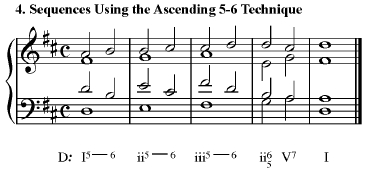

It can be seen that this sequence really is a variant on an ascending sequence with voice-leading chords—look at the examples above. This particular sequence comes out of contrapuntal voice-leading considerations and is in fact quite old; it is as much a result of avoiding parallels as it is a harmonic progression.

Due to voice-leading consideration, the ascending 5-6 sequence really works best in 3 voices, not four. This example would be more typical of instrumental writing than vocal writing, although it is perfectly possible as vocal music.

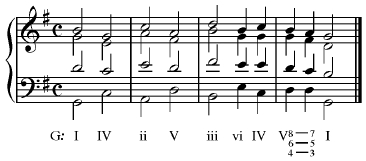

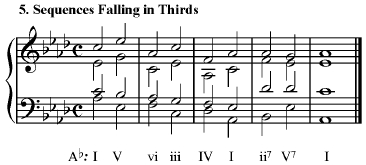

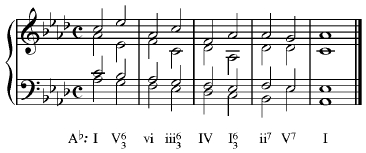

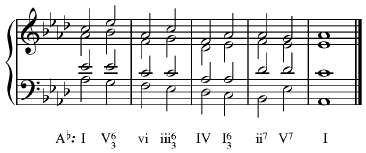

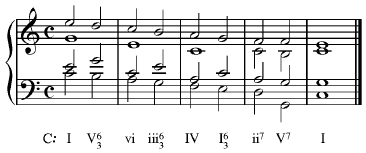

The sequence falling in thirds can be mistaken for an ascending fifths sequence if one Is careless.

Note that, while the pattern itself ascends a fifth, the distance from one pattern to another does not. Each pattern is a third lower than the one preceding it.

Although sequences falling in thirds can be written with all-root-position chords, it is more common for such sequences to be written with the second chord of the pattern as a 63 triad. The advantage is obvious and dramatic: a stepwise descending bass line.

Time to create a bit of a sensation. This voice-leading is quite smooth and takes advantage of common tones. There is, however, an overlap in the two upper voices moving from iteration to iteration. Remember that overlaps are not illegal; they can be used if circumstances warrant them. Here’s one such circumstance: between iterations they do not produce an unpleasant effect.

Not only is a stepwise bassline possible, but so is a stepwise soprano, moving in tenths above the bass!

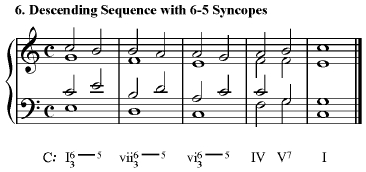

This is a relatively unusual sequence, but it works rather well. It works especially well in a 3-voice texture; note that the tenor line could be omitted entirely without doing any harm to the progression. It’s worth knowing this sequence, if only for Aldwell-Schachter’s flamboyantly overdone term for it. ‘6-5 syncopes’, indeed.