Aldwell-Schachter Chapter 30

Click on a musical example for playback

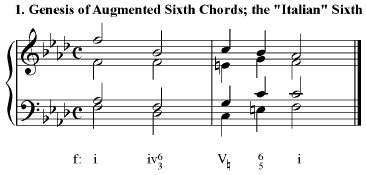

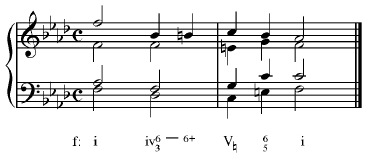

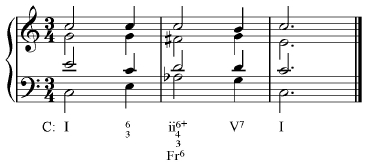

Genesis of an augmented sixth chord. Step 1: start with a iv6 in minor, moving to V.

Step 2: the sixth of the iv6 moves chromatically upwards as a passing tone.

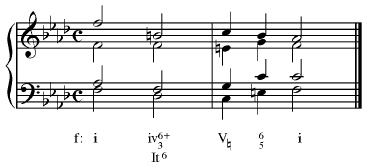

Step 3: the unaccented passing tone of Step 2 becomes the soprano itself. The sixth of the iv6 has been augmented, and thus we have an augmented sixth chord. This simplest form of the augmented sixth chord is called the Italian augmented sixth, or “augmented 6/3”.

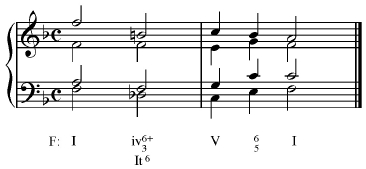

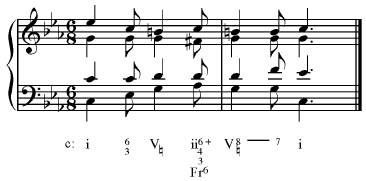

Augmented sixth chords work equally well in major. They do require more modifications: note that ^6 has been lowered. Nonetheless, the chord remains an augmented iv6—the augmented 6/3.

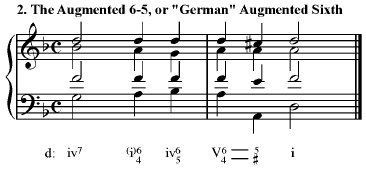

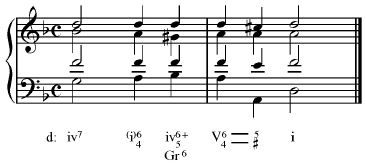

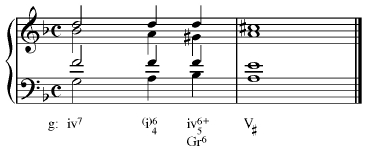

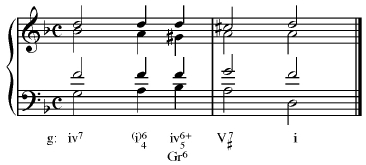

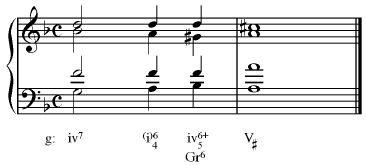

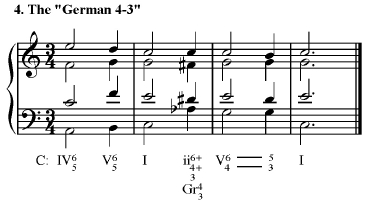

We begin with a progression in which iv7 moves to iv6/5 through a passing 6/4.

A chromaticized voice exchange between alto and bass produces the augmented 6/5, also known as the German augmented sixth chord. The resolution of the German sixth generally prefers the cadential 6/4 over a dominant. The next few examples will demonstrate the reason.

Resolving an augmented 6/5 directly to the dominant will produce parallel fifths.

One solution is to move the augmented 6/5 to a dominant seventh chord rather than a dominant. Note, however, that this could not be used for a semicadence since the dominant seventh is unsuitable for that purpose.

Another solution is to write an incomplete dominant triad, as here. NOTE that occasionally composers simply give up and write the parallel fifth, going to some extremes to mask it within the texture.

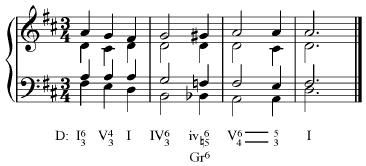

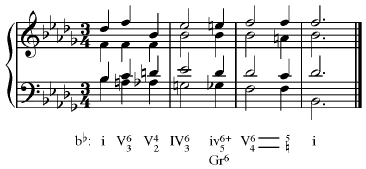

Here is a nice robust example of an augmented 6/5 in major. Note that all but one of the notes require a chromatic alteration to write this chord.

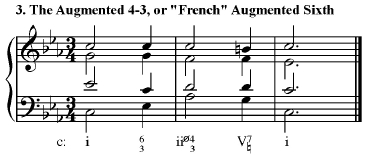

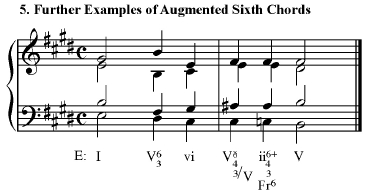

The augmented 4/3, or French augmented sixth chord, is a modified ii4/3. Here we start out with a progression in which ii4/3 moves to V7.

Raising the 6th of the ii4/3 turns this into an augmented sixth chord. Because the F# has such a leading-tone-ish quality, I have moved to V instead of a V7, although it would have been possible to move to a V7.

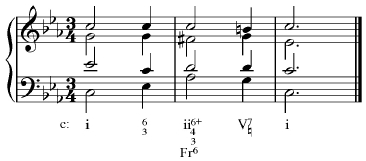

The augmented 4/3 works just fine in major as well; note that the bass note requires being lowered.

Sometimes a composer will write an augmented 4/3 with the fourth of the chord doubly augmented. The resulting chord sounds just like the German 6-5, but is spelled as a 4/3. It tends to occur when moving to a major 6/4 chord—thus the D# in the tenor leads more convincingly to E.

The augmented ii4/3 is similar to V4/3 of V; that similarity is exploited in this example, as V4/3 of V becomes augmented ii4/3.

This elaborate progression makes use of a major IV6 which is then altered into a German augmented sixth chord.

Contrapuntal considerations can sometimes win out over harmonic motion: here an augmented 4/3 is treated as an upper neighbor to V, so it is used to expand the dominant.

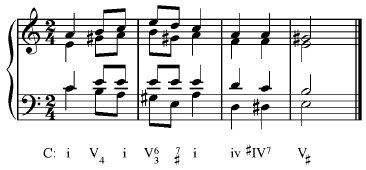

This is an example of an inverted augmented sixth chord. Such inversions are generally restricted to a root-position IV7, as this example shows. Normally you will analyze them as #IV7, with whatever modifications might be needed to indicate the seventh or third. Although strictly speaking these do not contain an augmented sixth, they sound so much like augmented sixth chords—and behave the same way—that it is customary to refer to them as “inversions” of augmented sixth chords, although technically they’re in root position.

Composers occasionally misspell augmented sixth chords, particularly spelling the German 6/5 as a dominant seventh chord. This example comes from Chopin. It is important to look at the function of the chord, rather than its spelling, to understand it in context. (My analysis goes with the function, rather than with Chopin’s spelling.)

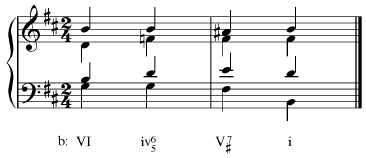

The Neapolitan (Phrygian) and augmented sixth chords can work well together. Here a Neapolitan 6/4 prepares an augmented 6/5.