Aldwell-Schachter Chapter 29

Click on a musical example for playback

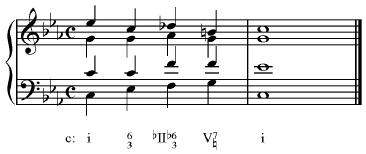

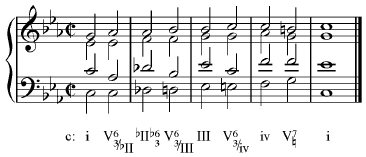

A plain example of the Phrygian II6, also known as the Neapolitan sixth. Note the ^b2-^7 movement in the soprano, which is typical of the Phrygian II progression. It is generally best to double the bass note of the Phrygian II. Note how different Db-B sounds from C#-B!

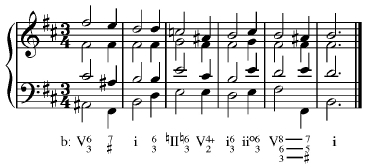

Phrygian II is essentially the supertonic and can occur more or less interchangeably with ii6. Because the flattened ^6 of the chord occurs normally in minor, it occurs more often in the minor mode. Here a Phrygian II leads to V4/2.

The same progression works equally well with vii4/3 instead of V4/3—just as it would work well with V4/2. Note that the use of the Phrygian II creates a potential cross-relation, but since the C to C# occurs between outer and inner voices, the effect is not at all objectionable.

Here the Phrygian II passes through a vii7/V and then lands onto a cadential 64. This allows a rather nice ^b2-^1 motion in the tenor.

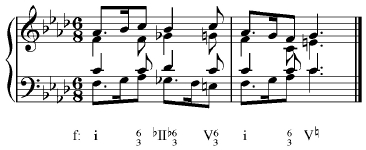

The flattened ^2 does tend to govern other notes as well. This progression uses a lowered V6, followed by iv6, flattened iii6, and finally the flattened ii6—a progression of 6/3 chords, all of them modified. It works just fine and is in fact similar to the Mozart example given in the text.

Although bII in root position is rare, it works very well in motion towards V6, V6/5, or vii7. It does not move well to root-position V due to the tritone leap that results.

The Phrygian II is less common in major keys but is highly effective nonetheless. It requires modifying both ^3 and ^6 in order to work.

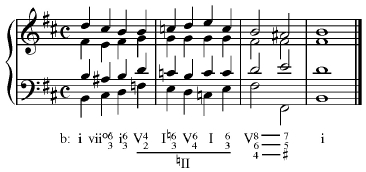

The entire Phrygian II can be tonicized. This is really quite a common progression, found in Viennese Classical composers, for example. Here the second measure tonicizes bII with its V42, and then leads on to the cadential 64.

A rare but useful progression: the use of bII to gloss over the awkwardness of an ascending sequence in minor. Instead of the usual diminished ii, we have a major chord.

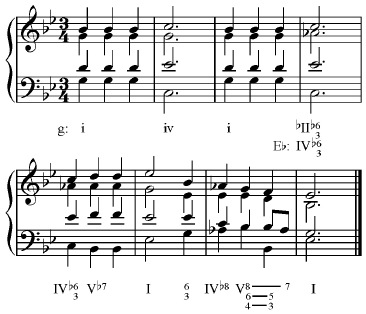

Shock value! Phrygian II does not contain notes common to two keys and thus would not be a likely candidate as a pivot chord. Its very unsuitability makes it an ideal candidate for a shock-treatment modulation. Composers fond of this kind of kamikaze modulatory approach are Haydn, Beethoven, and Schubert. The example here would not be at all out of place in a Schubertian scherzo movement.